Every few years, a revolutionary way of treating OSA comes out. Nineteen eighty (1981) was a pivotal year in sleep medicine when Dr. Colin Sullivan reported reversing a vacuum cleaner motor to provide positive pressure through a makeshift mask to treat severe obstructive sleep apnea. Dr. Shiro Fujita also described a palatal operation to treat obstructive sleep apnea in 1981. Later on, oral appliances were also introduced. Over the years, advances were made with positive air pressure as well as with multi-level soft tissue and jaw procedures.

In 2014, the Inspire hypoglossal nerve stimulation procedure received FDA approval for patients in the United States. In their pivotal trial with results published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2014, they reported a 68% drop in the average apnea hypopnea index (AHI), 70% drop in the oxygen desaturation index (ODI), and with an overall “response” rate of 66% (more than 50% drop in the AHI and less than 20).

In 2018, a group of surgeons performing this procedure published their 5 year outcomes. One hundred and twenty six patients were followed for 5 years, and 97 were included in the study, with 71 available sleep studies. Comparing from baseline to 12, 36 and 60 months, improvements across all measurements remained stable. The pre-treatment AHI was 32, dropping to 15, 11 and 12, at 12, 36 and 60 months, respectively. The functional outcome of sleep questionnaire (FOSQ, a validated sleep quality of life tool) increased significantly from 14 to 17, 17 and 18. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale dropped from 11.6 to 7 at all follow-up periods. Now, this procedure is being performed at over 300 centers in the United States and more and more insurance carriers are covering it, usually after a preauthorization process.

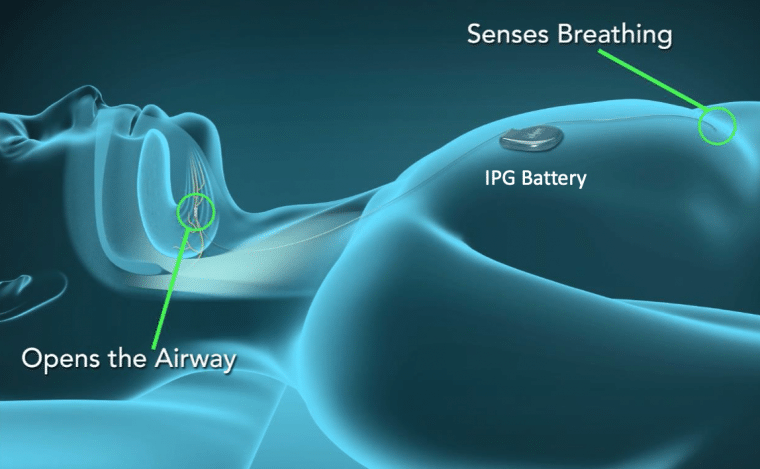

Technically, the pacemaker is implanted under the skin beneath the right collarbone, as opposed to a heart pacemaker, which is implanted on the left side. It’s a similar sized container. A small incision is made under the right chin, and the nerve that supplies the tongue (hypoglossal nerve) is exposed. This technique is very similar to a common procedure we perform in our field to remove the submandibular gland for stones, infections, or cancer. Once the nerve is identified under a microscope, a nerve stimulator cuff is placed around a specific area of the nerve that protrudes the tongue. Another small incision is made on the right ribcage and a breathing sensor is placed. The tongue nerve cuff and respiratory sensor are then connected to the chest neurostimulator under the skin. Essentially, it senses when you make an effort to breathe during sleep, and stimulates your tongue to keep your throat open. There is a remote control that can control the setting and timing functions as well.

These results are in line with published data for multi-level soft tissue procedures. However, the recovery process is faster with significantly less pain and discomfort. It is performed as same day surgery, and the device is activated at one month post-op and fine tuned in the sleep lab in 2 months. The battery lasts 11 years, and can be changed in an outpatient procedure.

Although this procedure may sound like a magic bullet for people with sleep apnea, it’s not for everyone. There are a handful of inclusion criteria to be eligible for this procedure. First of all, you must have tried and refused CPAP. The AHI has to be moderate or severe (AHI between 15 to 65). Your sleep test has to be performed within the past 2 years. Your BMI has to be under 32. Lastly, you’ll need to undergo drug induced sleep endoscopy to see the pattern of soft palate collapse. If it collapses in the front to back manner, then you’re a candidate. If it closes in a concentric or circumferential manner, you’re not a candidate. The main reason for this last criteria is that when the tongue protrudes forward, it pulls on a muscle attached to the side of the tongue that connects to the soft palate, called the palatoglossus muscle. If the soft palate is too floppy, relaxed or redundant, the tongue movement won’t open the soft palate as well.

What this means is that this procedure will apply to only a small minority of sleep apnea sufferers, excluding most overweight people. Additionally, you have to be willing to be implanted with a device, something not everyone will feel comfortable with. I counsel inquiring patients that the success rate is good, but not perfect, with about 10% of people not getting the full benefits desired. There is also the potential risk of anesthesia and surgery in general.

If you can’t tolerate CPAP and you meet the other criteria and you’re willing to consider an implantable pacemaker, then this option may be a good one.

** This post was originally published on http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/doctorpark/~3/Jnr5NO_Az3k/a-tongue-pacemaker-for-sleep-apnea-high-tech-hope-or-hype